sense of value_2024

Palais des paris, Japan. 2024

Extract from an interview with #palaisdesparis #fredericweigel#yoshikosuto

“For about five years, we’ve been exploring the concept of value, particularly in the context of contemporary art—not in the sense of traditional or family values, but as an economic and phenomenological idea. Our focus has been on how value impacts the perception of and relationship with works of art.

According to Marx, value is relational and social, meaning it doesn’t exist intrinsically within an object but is rather an emergent feature. To break it down as simply as possible, Marx described value as having two components: use value and exchange value, both of which are present in all commodities. For instance, when someone makes a chair for personal use, use value has been produced. However, once the chair is offered for sale or exchange, it enters the market, and its value is no longer just about its usefulness to the individual. Instead, the chair now possesses exchange value, which is determined by its relationship to other products in the marketplace. This value is comparative, influenced by factors like supply and demand, production cost, the labor required to make it, and the value of other commodities that might be exchanged for it. This process „flattens“ the object, stripping away its history and the social relations embedded in its production. This phenomenon, known as reification, affects all commodities but has a particular impact on artworks, fueling all kinds of feticist fantasies, such as the myths about the magical nature of art, the artist as creator or genius, etc. Reification refers to the process by which social relations, human labor, or human creativity are objectified.

In the art world, every player—museums, galleries, critics, curators, etc.—contributes to this creation of value. While this is a natural part of the art ecosystem, it does lead to distortions in both the production and perception of art objects. We’ve hypothesized that the value of an artwork, as perceived by others, is as crucial as the concept behind it or the material that constitutes it. These three elements—value, concept, and materiality— are shaped by historical and cultural contexts but also deeply intertwined, and it’s essential to critically engage with the notion of value just as we do with the other elements. Ignoring this diminishes our understanding of what an artwork truly is.

Contemporary art, like any commodity, is produced within a society that measures it by its value, reflecting the dominant mode of production. However, a key difference is that while most commodities eventually end up consumed, discarded, and finally in the trash, artworks hold the promise of salvation to death, longevity, being transmitted through generations and reaching a higher purpose, resisting the decay of time through the symbolic values they embody, even if this remains hypothetical. Thus, contemporary art, like modern art, can be seen as somewhat schizophrenic: it is scatological and eschatological at the same time, as already sensed by Manzoni and others. The contemporary art object carries several types of value: the traditional value rooted in its historical status, the legacy it gathers over centuries, and the more recent commodity value, encompassing use, symbolic, and exchange value. These layers of value coexist within the artwork, creating tension and complexity in how it is perceived and how relationships with it are built.

For this project, we began a collaboration with the Palais des Paris in Takasaki, Japan, which proved to be really valuable. We engaged in discussions with Yoshiko Suto and Frédéric Wiegel, who offered sociological and academic insights. They had studied the positioning of contemporary art in Japan and abroad, as well as the relationship between these contexts. This helped us begin our work by addressing the clichés and mutual fantasies that arise when an artist arrives in Japan and the Japanese respond to a foreign artist’s work. We quickly decided on a entry-strategy. Our challenge was to embrace our identity as foreign artists in Japan and find our place within the Japanese contemporary art scene. The idea was to create a project that mirrored the process of value creation in Japan, incorporating this dual perspective. It felt a bit like adopting a camouflage. We decided to start by positioning ourselves as European artists arriving in Japan and experiencing the gaze of the Japanese art world. It was intriguing to see that the Japanese contemporary art scene almost instinctively selects artists who validate aspects of Japanese national identity and traditional japanese beauty. For example, many artists incorporate traditional Japanese crafts—such as ceramics, textiles, or color production—into their contemporary art, making this approach quite common. Often, artists do this with genuine admiration for tradition and reputed artisanal skills. We were interested in revisiting this path for our work.

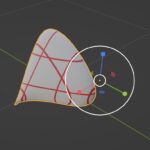

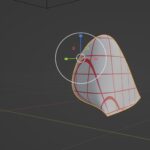

Choosing the right techniques was challenging. We wanted to create something that would reconstruct the value creation process in a broader sense—how a concept transforms into material form. We started with the idea of a diagram, a motif prevalent in contemporary art, especially among artists from the 60s and 70s, which mimics the dimensional reduction that commodities undergo to enter the market, as Marx described. Any object put into a diagram is flattened and measurable. There’s a connection between art, diagrams, commodities, and exchange value. Our goal was to explode and reproduce this diagram in a sort of mega-diagram by creating a 3D structure of it, the lattice structure embodied in matter.

We discovered in Japan a technique for crafting a block of wood with various colors, used to create geometric decorative figures that suited our purpose: the Yosegi technique, a very old one. At the end of the Yosegi-making process, the artisan uses an iron tool to carve a thin, almost transparent slice, which to us resonates with the reverse process: turning a 3D object into something subtle and close to pure bidimensionality. Though this process may seem complex, it ultimately culminated in a sculpture. The prototype of this sculpture demonstrates how, within this mega-diagram, the artist carves out interesting, sometimes counterintuitive forms that are nonetheless pleasing. By taking on the role of artisans, we rediscovered something inherently decorative. We wanted to create something abstract, free from heavy symbolism, that would harmonize with the patterns that emerged.

An interesting side note: the Japanese postal service refuses to send sculptures or artworks in general. At the end of our residency, we were reminded again of the Brancusi case vs the U.S., which started with Marcel Duchamp transporting Brancusi’s Bird sculptures in a suitcase to New York. Customs held them up because the Bird sculptures looked more like kitchen furniture and didn’t appear to be artworks. Of course, it was all about taxes, and we like to imagine Duchamp trying to convince customs that the objects he was carrying were indeed artworks. We considered recreating this scenario by sculpting the artist in the form of Brancusi’s sculpture style. Brancusi represents an archetype of modern sculpture, and it will be interesting to see how customs or the post office respond when we ship the sculptures back to Europe.”